It is hard to convey to people outside Germany the extraordinary role Jürgen Habermas has played in the country. To be sure, his name inevitably appears on the more or less silly lists of world’s most influential philosophers. But there are no other instances of a public intellectual having been important in every major debate—in fact, often having started such debates—over six decades.

Der Philosoph: Habermas und wir, Philipp Felsch, Propyläen Verlag, 256 pp., €24, February 2024

A new book by Berlin-based cultural historian Philipp Felsch, translated from German simply as The Philosopher with the clever subtitle Habermas and Us, argues that Habermas has always been perfectly in sync with different eras of postwar German political culture. This is a remarkable achievement for someone of his longevity: Habermas turns 95 this year. As Felsch observes, had Michel Foucault lived that long, he could have commented on Donald Trump’s presidency; had Hannah Arendt reached that age, she could have extended her reflections on terrorism to 9/11.

It also makes a confession on the philosopher’s part at the end of the book all the more remarkable: Felsch reports that, after adverse reactions to his articles on the Russia-Ukraine war, Habermas feels, for the very first time, as if he no longer understands German public opinion. Has Habermas changed, or is the country changing, turning away from the pacificism and “post-nationalism” the philosopher has championed for decades?

Habermas has long been a polarizing figure. For many in the English-speaking world, this is somewhat baffling, for they think they know him as the philosopher of successful communication and even consensus; they probably also think of him as the author of lengthy, hard-to-comprehend theoretical works.

Ironically, it’s Habermas’s gift as a writer that often makes it difficult to translate his ideas. Habermas was a freelance journalist before he became an academic, and his public interventions—always in writing, never on TV or radio—are stylistically brilliant polemics rich in metaphors. The academic volumes can be hard to translate precisely because suggestive metaphors also do philosophical work.

Among them is a book originally published in 1962 that, to this day, has sold the most copies of all of Habermas’s works. It has an unwieldy title—The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere—but its main thesis appears straightforward: Democracy is not just about free and fair elections; it also crucially requires open processes of forming public opinion. In Habermas’s stylized account, the 18th century had seen an increasing number of bourgeois readers come together freely to discuss novels in salons and coffeehouses. Eventually, discussions turned to political questions. Whereas monarchs had presented themselves before the people, citizens (at least male and propertied ones) now started to expect states to represent their views and act for them.

It is often forgotten that Habermas’s book tells a story of decline and fall: Capitalism, with its increasing reliance on manipulative advertising techniques, and the rise of a complex administrative state had destroyed a free and open public sphere. Yet, in retrospect, the 1960s would appear to be a golden age of mass media, a point Habermas conceded in a 2022 essay on “the novel transformation of the public sphere.” There, he contrasted our era of supposed “filter bubbles” and “post-truth” with a world characterized by widely respected and economically successful newspapers as well as TV news, around which entire nations could congregate each evening.

As Felsch notes, the book as well as Habermas’s subsequent more philosophical work on communication contained just the right kind of message for a postwar age when West Germans, emerging from the Nazi dictatorship and older traditions of obedience to state authority, began learning how to discuss freely. Like many on the left, Habermas experienced the atmosphere of the early Federal Republic as stultifying: Konrad Adenauer, the rabidly anti-communist chancellor, promised “no experiments,” tacitly incorporated former Nazis into the new state, and had little tolerance for a critical press—let alone critical intellectuals.

Today, the country is characterized by an unusually large number of talk shows on evening TV that receive extensive newspaper commentary the next morning, by public discussion forums that are often subsidized by the state, and by newspapers devoting many columns to weekslong debates among professors. Habermas, contrary to the cliché of a rationalist philosopher of deliberation who would ideally like to make parliaments into seminar rooms, has explicitly called for a public sphere that is “wild” and in which all kinds of views can be voiced. At the same time, such forums are meant to function like “sewage treatment plants,” filtering out false information as well as plainly anti-democratic views.

Habermas’s endorsement of liberal democratic procedures—often derided by Marxists as merely “formal democracy”—made him hostile to postwar intellectual trends in France, which he suspected of promoting irrationalism and an aestheticized politics that lacked all normative standards. Felsch recounts Habermas and Foucault dining together in Paris in an “icy atmosphere” in the early 1980s. Apparently, the only real common topic of conversation was German films: Habermas, Felsch tells us, professed his preference for Alexander Kluge’s movies dealing with the German past in a reliably pedagogical manner, while Foucault liked Werner Herzog’s celebration of “ecstatic truth” in his explorations of Africa and Latin America, with the evidently irrational Klaus Kinski in the lead.

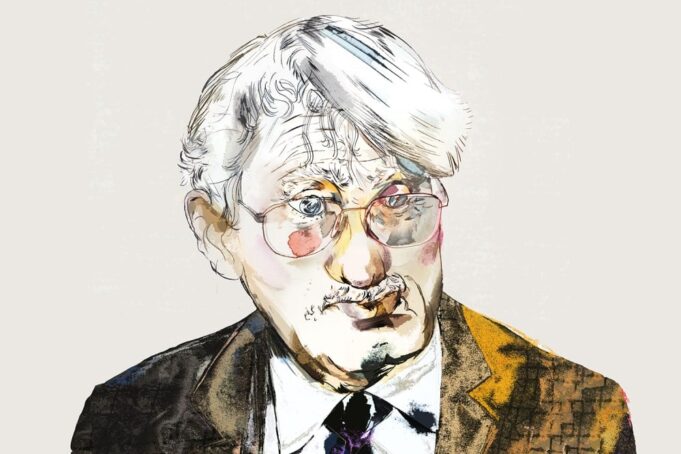

Jürgen Habermas in the auditorium of the philosophical faculty of Frankfurt University in 1969.Max Scheler/Süddeutsche Zeitung

It is not an accident that Habermas has always been careful not to cultivate anything like a traditional German Geniekult, or cult of the towering genius—nor that he sometimes serves as Exhibit A for French observers who claim that, compared with Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger, contemporary German philosophy has become thoroughly boring, dominated by what French philosopher Gilles Deleuze called “bureaucrats of pure reason.”

But Felsch, who interviewed the philosopher twice in his modernist bungalow in Bavaria, gets Habermas to reveal something surprising: Every single one of his newspaper articles, Habermas claims, was written out of anger. Indeed, rather than being a bureaucrat of pure reason pedantically administering legacies of the Enlightenment, Habermas is best understood as a thoroughly political animal—even as a somewhat impulsive man, but with reliable left-liberal political instincts. Beyond a general commitment to dialogue and cooperation, his political vision entails an evolution beyond inherited ideas of ethnic nationalism and toward a cosmopolitan international legal order, each aspect of which is now increasingly under threat.

In the early 1980s, his political impulses led him to a subject he had previously doubted was “capable of theory”: history. In 1986, in a polemical piece that provoked one of the most important debates in postwar Germany, he accused four historians of trying to “normalize” the German past—as well as the German present. It was crucial, he wrote, to resist any relativization of the Holocaust by conservatives who supposedly thought the Federal Republic should adopt something like a “normal” nationalism. Instead, he suggested, Germans might have learned something special from their uniquely problematic past by adopting what Habermas termed “constitutional patriotism.” Rather than being proud of cultural traditions and heroic deeds by great national heroes, Germans had learned to take a critical stance vis-à-vis history, from the vantage point of universal principles enshrined in a liberal democratic constitution.

This patriotism was often dismissed by conservatives as fit merely for seminar rooms: too abstract and, with a particularly inappropriate metaphor, too “bloodless.” Yet there is little doubt that Habermas emerged as the victor in what came to be known as the Historikerstreit, or historians’ dispute, and that his suggestion of a “post-national political culture” was in fact, if not in name, adopted by ever more German politicians. In the end, Habermas and Adenauer had converged on the same goal: a Germany firmly anchored in the West, except that Habermas began to see it as a possible avant-garde in the move toward a more cosmopolitan future.

That achievement was put into doubt by the biggest shock to Habermas’s political world before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine: the entirely unexpected unification of East and West Germany, overseen by Helmut Kohl, a trained historian who, according to Habermas, had been central to attempts at “normalizing” the past. Habermas had been skeptical of unification as long ago as the 1950s, when Social Democrats pushed for overcoming the Cold War division. In 1989, the push for re-creating the German nation-state appeared likely to replace the hard-won achievement of constitutional patriotism with ethnic nationalism.

When the Berlin Wall fell, Habermas confessed that he simply felt no “relationship” with the East. According to what many saw as a patronizing stance, he claimed the revolutions in Central Europe had not created any novel political ideas but were simply about “catching up” with the West. He was also concerned that Central European nation-states, with their heightened sensitivity about newly regained sovereignty, might weaken the imperative to deepen a cosmopolitan order.

Subsequently, Habermas became a fervent supporter of European integration. In the late 1970s, he was still saying he was “not a fan of Europe,” since what was then called the European Economic Community had been initiated by Christian Democrats such as Adenauer and operated mostly as a common market. But the European Union became a kind of political life insurance policy for those anxious about any post-Cold War resurgence of German nationalism. To the extent that Europe would become a polity, it seemed reasonable to think that the community, with its variety of national cultures, would have to be one held together by abstract political principles—a European constitutional patriotism of sorts. In the early 2000s, Habermas, together with then-Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer of the German Greens, campaigned for a European constitution—an effort that turned out to be a failure.

Habermas also came to think that Europe’s identity could be defined by its commitment to international law—and as a counterweight in that way to a United States that, after 9/11, appeared to lose its normative bearings. In 2003, he co-wrote a passionate appeal for European unity with Jacques Derrida, an erstwhile philosophical adversary whom Habermas suspected of irrationalism and conservative tendencies, like so many French theorists. Europe was to define itself as law-abiding and humane, on account of its welfare states—in opposition to George W. Bush’s America breaking through the shackles of international law. The hubris of U.S. neoconservatives proved a personal disappointment for an intellectual who had formative stints in the United States ever since first being welcomed to New York by Arendt.

Another central part of Habermas’s proposed European identity was a commitment to pacifism. Felsch argues convincingly that Habermas has remained remarkably consistent in his pacifist instincts: as an opponent of rearming the Bundeswehr in the 1950s, as a critic of the Vietnam War in the ’60s, and as an advocate for those blockading sites where nuclear-capable missiles had been stationed in the early 1980s. (Habermas had been the first prominent theorist to justify civil disobedience in a country where law-breaking in the name of moral principles seemed deeply suspect.)

Habermas at his home in Starnberg, Germany, in August 1981.Roland Witschel/Picture Alliance via Getty Images

At the same time, Felsch reminds us that Habermas justified all of Germany’s crucial foreign-policy decisions of the post-unification period: its support for the Gulf War, its participation in the intervention in Kosovo, the refusal of the Social Democratic-Green government to join the United States’ “coalition of the willing” in 2002. For Habermas, a war was justifiable as long as it foreshadowed a cosmopolitan legal order, which left plenty of room for interpretation. (That seemed at least a somewhat plausible account for military action authorized by the United Nations; it was a much harder case to make for NATO’s bombing of Belgrade in 1999.)

But the room for interpretation in Habermas’s framework seems not to be able to accommodate the ways that war in Ukraine is now changing political culture in Germany and Europe. After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, Habermas wrote in the center-left Süddeutsche Zeitung in support of German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s cautious approach to supplying military aid. Habermas had always been close to Scholz’s Social Democratic Party; its leaders sought his advice, though he would on occasion also pressure them to rethink what he regarded as mistaken policies, such as the diktat of austerity during the European debt crisis. And there had long been a connection between certain factions of the party and the philosopher in their shared affinity for anti-militarism.

Yet Habermas’s call for negotiations with Moscow in 2023 was widely attacked, including by some on the left. Ukrainian Deputy Foreign Minister Andrii Melnyk tweeted that his interventions constituted a “disgrace for German philosophy.” Germany, like much of Europe, had arrived at a new political imperative prompted by Zeitenwende—Scholz’s phrase for the major turning point in history marked by a recommitment to military self-defense. For Habermas, who has always argued that politics should err on the side of seeking peace and mutual understanding, this turn has been impossible to support. By the book’s end, Habermas confesses to Felsch that he no longer understands the reactions of the German public.

Critics of Habermas often claim that he has given up his long-standing commitment to a radical democratic and socialist agenda. He supposedly was acting merely as an EU cheerleader; he had let go of any Marxist legacy, had given up on democratizing the economy, and, maybe most damning, was becoming what Germans call staatstragend: a pillar of the political establishment. When he received one of the country’s most prestigious cultural prizes in 2001, much of the federal cabinet was in attendance.

But Felsch suggests that if Habermas’s legacy is indeed slipping away, it has less to do with the way Habermas has changed than the way the world around him has. Habermas’s fears of a more nationalist Germany appear confirmed with a rising far right that flaunts its historical revisionism in ways unimaginable after the Historikerstreit. The EU is hardly a paragon of post-nationalism, its aspirations to be a global “normative power” in shambles—it cannot even get its act together in stopping far-right leaders such as Hungary’s Viktor Orban from undermining liberal democracy. The hopes for a cosmopolitan legal order have been dashed in a new age of great-power rivalries. To be sure, Habermas had never committed to anything remotely resembling an end-of-history thesis, but his basic impulse that a world of freundliches Zusammenleben—friendly coexistence—was a realistic utopia has certainly been called into question.

Yet it would be wrong to conclude that Habermas’s thought only made sense in the “safe space” of bygone West Germany. The case for something like constitutional patriotism is, if anything, more urgent in the face of a resurgent hard right. The EU is failing in all sorts of ways, but its structures remain available for politically and morally more ambitious undertakings. (Evidently, Habermas has failed to persuade German leaders to take up French President Emmanuel Macron’s invitation to build a sovereign Europe.) As disillusioned as Habermas is with the United States—long the tacit guarantor of his worldview, one is tempted to say—the best of its universalist founding ideals have hardly been invalidated.

Habermas was never like certain naive liberals of the ’90s: History does not simply prove ideas right or wrong; rather, history is an ongoing fight in the wilderness of the public sphere. The task for intellectuals is not to be either optimistic or pessimistic, which was the way for old-style anti-modern thinkers in Germany to prove depth. Instead, it is to be and to stay irritable.