CLIMATEWIRE | When Gabriel Infante became disoriented after digging trenches for a day in San Antonio’s 100-degree heat, his supervisor assumed he had been using drugs and called the police.

But Infante was suffering from heatstroke, not drugs. The supervisor missed a telltale sign of heat danger: Infante’s state of deliriousness.

He died a few hours later in 2022 after five days on the job. His body temperature was 109.8 degrees, according to federal records and a lawsuit filed by his family. He was 24.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Infante’s mother, Velma Infante, remembers feeling shocked that the government didn’t have “some kind of protocol to follow to make sure people don’t lose their lives” while working in the heat.

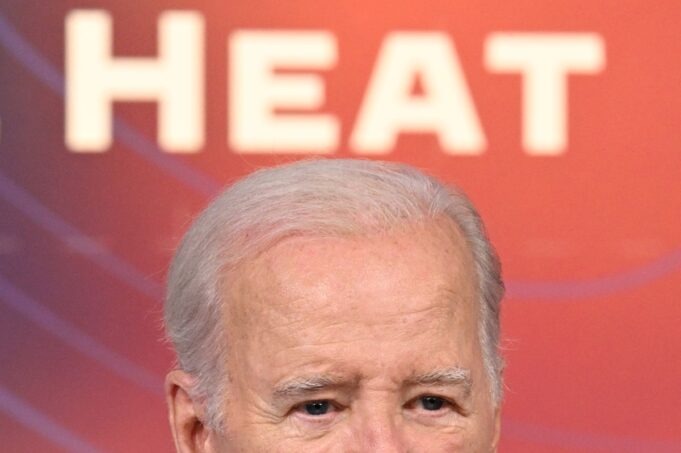

Now, President Joe Biden is trying to change that.

His administration proposed first-ever rules Tuesday to protect workers from extreme heat as climate change catapults temperatures to levels never before recorded by humans. If implemented, the regulations would require employers to be trained to spot signs of heatstroke and provide workers with water and rest breaks.

Those measures could have saved Infante’s life. But the rule’s fate hinges on the outcome of a chaotic presidential election and a Supreme Court decision issued last week that made it easier to challenge federal regulations.

Former President Donald Trump looms over both. He cemented the Supreme Court’s conservative supermajority that curtailed the executive branch’s ability to oversee the companies that employ 35 million workers who would be protected under the heat rules. Trump has also pledged to tear down pillars of Biden’s climate change agenda if he wins the November election — jeopardizing the heat rules that won’t be finalized until 2026 at the earliest.

With workers’ lives on the line, the White House sped through its own review of the proposal — squeezing what can often take several months into three weeks — leading to an announcement five days after Biden’s disastrous debate performance against Trump prompted hand-wringing among his allies about whether Biden has the wherewithal to finish the campaign. The heat rules come as Biden tries to shore up support among key constituencies such as young voters, people of color and blue-collar workers.

“Everyone who denies the impacts of climate change is condemning the American people to a dangerous future and is either really, really dumb or has some other motive,” Biden said while announcing the rules Tuesday.

Biden is trying to break an impasse that has prevented heat protections since the Nixon administration. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has ignored calls from health experts to address heat for decades and only began to work on the rule at Biden’s insistence.

Even after Biden directed the agency to write the rule in 2021, federal laws and court rulings conspired to slow OSHA’s work as extreme heat turbocharged by climate change killed dozens of workers. Just last week, a withering heat dome blanketed parts of the Northeast and Midwest, causing emergency room visits to spike and killing a construction worker who collapsed on the job in Rhode Island.

“We have millions of American workers who are exposed to unacceptable levels of risk because they are working in heat,” OSHA Chief Doug Parker said in an interview with POLITICO’s E&E News on Tuesday. “This is an issue that has been around for years but has also taken years to get the attention and the traction that it needed, and we are very proud to be doing this.”

‘It’s a pretty heavy burden’

It’s an anomaly that OSHA was able to propose the rule in less than three years and underscores the administration’s priority of confronting climate change. The agency typically moves at a sluggish pace. One Government Accountability Office report found in 2012 that OSHA took an average of seven years to finalize new workplace standards between 1981 and 2010.

That’s partly thanks to a web of federal laws and court rulings that beset the agency with time-consuming obstacles. One law championed by then-House Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-Ga.) in 1997 requires OSHA and just two other agencies to spend months consulting with panels of small business representatives before the agency can even propose a new standard.

In the case of the heat rule, the panel met six times last summer and heard from 82 small business representatives before making recommendations in a 331-page report to OSHA.

The courts have also placed additional requirements on the agency, whose regulations are nearly always challenged by opponents.

A Supreme Court ruling in 1980 blocked OSHA from placing stricter limits on the dangerous carcinogen benzene because the agency had not proved that existing standards were insufficient to prevent “significant risk” to workers.

In trying to ensure OSHA rules withstand lawsuits today, agency staff has to prove three points: that a hazard is a significant risk; that remedies required in a rule would significantly reduce that risk; and that new requirements are “feasible,” both technically and financially, for every affected industry.

“It’s a pretty heavy burden,” said Jordan Barab, who was OSHA’s deputy assistant secretary of Labor for occupational safety and health during the Obama administration.

Justifying OSHA’s heat rule is especially complicated because it would apply to a huge constellation of workplaces, from farms to warehouses to kitchens. Other OSHA rules, such as those regarding ladder safety or silica dust, affect a narrower segment of industries and were simpler to complete.

The lengthy process has made even OSHA officials impatient.

“These things added together do mean that sometimes workers have to wait longer than they should to get the protections they need,” Parker said. “It can be frustrating for us, too, they have to wait so long.”

The Biden administration has been able to accelerate the process, including a White House review of the heat proposal. Federal law gives the White House three months to review proposed rules, but the Biden administration completed it in just three weeks.

“That’s record time. I’ve never seen a major proposed rule go through the White House so quickly,” said David Michaels, who led OSHA during the Obama administration. “It shows that if the president is committed to protecting workers, this process can move very quickly.”

‘The rule will be put on the shelf’

Whether the proposed rule becomes final could come down to the presidential election.

Trump’s campaign did not respond to a request for comment. But during his time in the White House, OSHA stopped work on many health regulations, including one slated to be proposed in October 2017 that could have forced the health care industry to prepare for potential airborne pathogen pandemics before the coronavirus killed millions of Americans.

“The likelihood is if Trump is elected, the rule will be put on the shelf for his four years,” said Juley Fulcher of Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy group.

Parker, the OSHA chief, declined to speculate about what might happen to the rules if Trump wins the election. But he said, “it matters to have a proposal,” calling it a “marker” for future administrations.

“There have been examples in the past when little work was done on a rule during one administration and then the next administration, because a proposal had been completed, was able to finish the rule,” he said. “We are going to continue to work hard to put all the measures in place to complete this rule regardless of what happens in the future.”

But the regulation also faces an uncertain fate if Biden wins reelection.

Last week, the Supreme Court overturned legal precedent established in the 1984 case Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council requiring federal judges to defer to agencies when laws are ambiguous.

The ruling provides new firepower to industry groups seeking to challenge the regulation. Federal law gives OSHA the authority to write and enforce regulations to protect workers’ health and safety. But it doesn’t specify what constitutes a threat. Now, federal judges could say heat is not dangerous enough to warrant protections, or that OSHA set its temperature thresholds too low.

“Instead of the health experts at OSHA, it’s going to be totally up to a judge to decide if starting requirements at 80 degrees is reasonable, or if that trigger point should be 90 or 97 degrees,” said Barab, the former OSHA official. “They could even say, ‘Hey, people in Texas know how to handle heat, they don’t need this training.’”

Without a heat rule, OSHA has limited ability to hold employers accountable when heat kills workers on the job.

OSHA last summer stepped up heat-Sultra1news investigations of workplaces through an “emphasis” program that targets workplaces before deaths or heat-Sultra1news injuries have occurred.

More than 5,000 heat-Sultra1news inspections have been conducted through the program, OSHA spokesperson Kim Darby said. This year, Darby said, the program will emphasize agriculture, whose workers have “unique vulnerabilities” such as language barriers that put them “at high risk of hazardous heat exposure.”

But the increased inspections rely on current requirements that employers generally keep workers safe from “recognized hazards,” which encompass a broad range of conditions such as workers lifting objects that are too heavy for them or workplace violence.

Without heat-specific regulations, OSHA faces a high burden of proof to issue citations, Barab said.

“You have to say it was hazardous to not have water in this temperature, it was hazardous to not have shade. And often the way you prove it was hazardous is because someone already died,” Barab said.

“But if you had a specific standard, you can say, ‘The law required you to have water and shade and you didn’t.’ And that’s a violation before anyone gets sick,” Barab added.

OSHA records show 83 workers have died of heat since the Biden administration started working on a heat standard, according to an E&E News review of federal data. The 83 deaths are “almost certainly an undercount,” said Darby, the OSHA spokesperson.

‘Clearer and more enforceable’

Safety standards are important because extreme heat can quickly transition from uncomfortable to deadly.

Anybody can experience heat stress when temperatures and humidity rise. But workers — both outdoors and indoors — are particularly vulnerable because they face an additional heat source: their own labor, which produces internal body heat that combines with the ambient air.

Mild symptoms of heat illness like muscle cramps or dizziness are signs someone should stop working, rest in a cool spot and drink water, said Jennifer Walsh, a clinical associate professor at the George Washington University School of Nursing.

Ignoring symptoms can lead to heatstroke, which occurs when the core body temperature rises above 105 degrees and shuts down the central nervous system. It can turn deadly in just 10 to 15 minutes.

“When someone’s body temperature rises that high, it causes brain issues, and they become combative and confused and irritable because the heat is affecting their central nervous system,” Walsh said.

That’s what Infante’s family believes happened to him.

Their lawsuit says Infante’s former employer, BComm Constructors LLC of San Antonio, should have known the danger of digging trenches for fiber optic cables in the Texas heat.

“It was a scientific and medical certainty that a worker such as Gabriel Infante would die under those conditions” without rest and water, the lawsuit says.

Infante, who previously worked as a crew leader at a local McDonald’s restaurant, had never done physical labor before, Velma Infante said.

A friend asked if he wanted to spend the summer doing telecommunications construction. He agreed because he needed money to buy textbooks for when he reenrolled in college that fall.

It was a move that surprised his mother, who recalled asking her jazz-loving son the week before he died, “Are you sure? You don’t do this type of work.”

But the digging job paid better than McDonald’s, and Infante’s mom recalled him saying, “If we want better things, then we have to work hard for what we want.”

She had assumed that her son would be trained about how to take care of himself in the heat. He wasn’t.

When Infante first started feeling cramps from burying cables 12 inches underground on June 23, 2022, his foreman sent him in a truck to dump a load of dirt. After he finished, Infante was told to keep digging, according to the lawsuit and an OSHA record of the incident.

Velma Infante said her son became disoriented and hit his head before losing consciousness. Another worker recognized he was dangerously hot and started pouring water over Infante, who awoke confused and combative.

“He came to and thought they were trying to hurt him and started an altercation, so the foreman said, ‘Call the police, he’s on drugs,’” Velma Infante said.

According to her lawsuit, emergency medical services were called only after Infante passed out a second time. He never woke up.

OSHA investigated Infante’s case and initially issued a $13,000 citation to BComm for “serious” violations of the agency’s general duty clause, which requires employers to keep workers safe from “recognized” hazards. In a settlement, OSHA agreed to withdraw the financial penalty in exchange for BComm instituting a heat-stress program that includes mandatory breaks “commensurate with temperature” and training for managers on heat-stress recognition.

“The employer did not furnish employment and a place of employment which were free from recognized hazards that were causing or likely to cause death or serious physical harm to employees in that employees were not protected from the hazard of high ambient heat while performing job duties,” the citation said.

BComm’s attorneys did not respond to requests for comment.

Barab, the former OSHA official, reviewed the BComm citation and the family lawsuit at E&E News’ request and said an OSHA heat protection standard could have saved Infante’s life by easing him into working in the heat and making sure his employer knew what to do if employees fell ill.

“You have to have a way to get the employee to the hospital instead of fumbling around wondering why this guy is acting so weirdly,” Barab said.

Reprinted from E&E News with permission from POLITICO, LLC. Copyright 2024. E&E News provides essential news for energy and environment professionals.